Note: This post is based on a talk that I was supposed to give at a local FOSS United meetup but couldn't due to health issues.

Prologue

"... This puts the future squarely in the hands of those who know computers not for what they are, but for everything they have the potential to be."

"Computers aren't the thing, they are the thing that gets us to the thing."

-- Halt and Catch Fire, S01E01, 2014.

This conversation between two protagonists in HCF describes two types of people in computing:

- Those interested in solving real-world problems using computers.

- Those interested in solving the meta-problem, e.g. building computers.

But this categorization isn't exactly black and white.

When people who can’t think logically design large systems, those systems become incomprehensible. And we start thinking of them as biological systems. And since biological systems are too complex to understand, it seems perfectly natural that computer programs should be too complex to understand.

We should not accept this. If we don’t, then the future of computing will belong to biology, not logic. We will continue having to use computer programs that we don’t understand, and trying to coax them to do what we want.

Instead of a sensible world of computing, we will live in a world of homeopathy and faith healing.

-- Leslie Lamport, "The Future of Computing: Logic or Biology", 2003.

This quote, out of context might seem like Leslie Lamport doesn't respect biologists. That isn't the intention at all. He's pointing out that computing, unlike biology, is entirely constructed by us; given enough motivation and competence one can understand computing down to the last bit flip that happens under the hood. Biology on the other hand has evolved over millions of years and we have no choice but to decipher it by painstakingly observing the natural world.

Engineers working on real problems need to understand meta-problem and engineers solving the meta-problem need to understand the real-world implications of their solutions. Nothing much happens in isolation.

Now, with these two seemingly unrelated quotes out of the way. The main topic for this blog is a paper that describes what is now more commonly known as "von Neumann Architecture". This architecture is used in almost every computing device on earth, so from today's perspective, the problem they solved was about as meta as it gets.

I will mainly use note-worthy snippets from the original paper and let the paper speak for itself.

The Paper

Preliminary Discussion of the Logical Design of an Electronic Computing Instrument

Arthur W. Burks, Herman H. Goldstine, and John von Neumann

Wait, why is it called "von Neumann" architecture when he is the third author on the paper? John von Neumann was quite a big figure in this era. Around a year before this report was published, one of the draft reports was "leaked" by Herman Goldstine.

That leaked draft written by von Neumann was supposed to be internal. So while this work was supposed to be the product of many individuals working on the project, von Neumann's name stuck around.

This leak also resulted in the work becoming unpatentable. It's hard to say with certainty now, but this leak very well could've accelerated progress in computing by one or two decades.

reference: Oral history interview with J. Presper Eckert

"Bit Flips"

Novel research can be understood in terms of bit flips. A "Bit Flip" is a change in a certain assumption from the status quo (reference).

E.g.

- The status quo assumes that network behavior has to be statically defined in hardware.

- It doesn't have to be that way, we can build software-defined networking to make networks more flexible.

So while reading any seminal paper, you'll surely find a "bit flip". The bigger the assumption that was flipped, the bigger the impact of the paper.

This paper has several such bit flips but I'll focus on two here to begin with:

1.2. It is evident that the machine must be capable of storing in some manner not only the digital information needed in a given computation such as boundary values, tables of functions (such as the equation of state of a fluid) and also the intermediate results of the computation (which may be wanted for varying length) of time), but also the instructions which govern the actual routine to be performed on the numerical data. In a special-purpose machine these instructions are an integral part of the device and constitute a part of its design structure. For an all-purpose machine it must be possible to instruct the device to carry out any computation that can be formulated in numerical terms.

The team working on this project had previously successfully built ENIAC. It was designed for a singular purpose: artillery table calculations. Their next machine was going to be a general-purpose computer.

1.3. Conceptually we have discussed above two different forms of memory: storage of numbers and storage of orders. If, however, the orders to the machine are reduced to a numerical code and if the machine can in some fashion distinguish a number from an order, the memory organ can be used to store both numbers and orders.

Computers before this paper had two different types of memory: "orders" and "numbers". As computers have moved past just being numerical calculation machines, we now call them "instructions" and "data".

Storing programs and data in reprogrammable memory meant that computers could now be reprogrammed without physically rewiring the computer.

Components

We now take a look at the description of components that were designed for the first general-purpose computer.

1.4. If the memory for orders is merely a storage organ there must exist an organ which can automatically execute the orders stored in the memory. We shall call this organ the Control.

The terminology of calling computer parts "organs" is gone now, but the "Control" here describes what we now commonly refer to as CPU.

1.5. Inasmuch as the device is to be a computing machine there must be an arithmetic organ in it which can perform certain of the elementary arithmetic operations. There will be, therefore, a unit capable of adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing. It will be seen in 6.6 below that it can also perform additional operations that occur quite frequently.

The arithmetic organ is modern-day ALU, the part inside the processor that is capable of doing arithmetic operations.

In general, the inner economy of the arithmetic unit is determined by a compromise between the desire for speed of operation—a non-elementary operation will generally take a long time to perform since it is constituted of a series of orders given by the control—and the desire for simplicity, or cheapness, of the machine.

They recognize before even building the first general-purpose computers, one of the biggest debates in computing hardware: RISC vs. CISC.

Should we build simple and cheap components that require multiple instructions to solve the problem? Or complex and costly components that require fewer instructions. Today it seems we are settling on a CISC-like interface with RISC-like internal implementation. Popular RISC architecture like ARM and CISC architecture like x86 both have fairly complex instruction sets but complex instructions are split into smaller "micro-ops" which is what the processor actually ends up executing.

To summarize, transfers into the memory will be of two sorts: Total substitutions, whereby the quantity previously stored is cleared out and replaced by a new number. Partial substitutions in which that part of an order containing a memory location-number—we assume the various positions in the memory are enumerated serially by memory location-numbers is replaced by a new memory location-number.

While describing operations on memory they describe what feels like pointers, but what we call pointers now is almost two decades away in the future. Instead of referring to memory location as a pointer, their design modifies part of instruction itself to implement "pointer" like behavior.

3.4. It is clear that one must be able to get numbers from any part of the memory at any time. The treatment in the case of orders can, however, be more methodical since one can at least partially arrange the control instructions in a linear sequence. Consequently the control will be so constructed that it will normally proceed from place n in the memory to place (n + 1) for its next instruction.

Instructions don't need to be scattered in memory, they can be loaded in a sequential manner and hence control moves from one instruction to the next. This behavior is now commonly associated with "Program Counter".

3.5. The utility of an automatic computer lies in the possibility of using a given sequence of instructions repeatedly, the number of times it is iterated being either preassigned or dependent upon the results of the computation. When the iteration is completed a different sequence of orders is to be followed, so we must, in most cases, give two parallel trains of orders preceded by an instruction as to which routine is to be followed. This choice can be made to depend upon the sign of a number (zero being reckoned as plus for machine purposes). Consequently, we introduce an order (the conditional transfer order) which will, depending on the sign of a given number, cause the proper one of two routines to be executed.

Sequential code itself can not implement repeated computations. So they came up with jump instructions which based on certain conditions can make a jump in control flow. This can be used to implement conditional branching and looping.

4. The Memory Organ

4.1. Ideally one would desire an indefinitely large memory capacity such that any particular aggregate of 40 binary digits, or word, would be immediately available—i.e. in a time which is somewhat or considerably shorter than the operation time of a fast electronic multiplier. This may be assumed to be practical at the level of about 100 μsec. Hence the availability time for a word in the memory should be 5 to 50 μsec. It is equally desirable that words may be replaced with new words at about the same rate. It does not seem possible physically to achieve such a capacity. We are therefore forced to recognize the possibility of constructing a hierarchy of memories, each of which has greater capacity than the preceding but which is less quickly accessible.

That's odd, their machine has a word size of "40 binary digits". The term "bit" was not mainstream yet, that happened a few years later when Claude Shannon published his work that created the field of Information theory.

They are talking about a memory latency of about 100 microseconds. Today memory latency can range from less than 1 nanosecond (L1 hit) to 100s of nanoseconds (L3 miss). So while it has improved by at least 3 orders of magnitude since inception, it still pales in comparison to speedup in other components. This is now known as the "Memory Wall".

The necessity of memory hierarchy using a series of caches, DRAM, and disk that we know today was envisioned at the birth of general-purpose computers. However, the memory hierarchy mentioned here is unlikely to be the transparent CPU caches that we know today. Instead, the movement of data between faster memory and storage was left to "planners" or programmers. Modern caching comes into the picture c. 1960s.

The most common forms of storage in electrical circuits are the flip-flop or trigger circuit, the gas tube, and the electro-mechanical relay. To achieve a memory of n words would, of course, require about 40n such elements, exclusive of the switching elements. We saw earlier that a fast memory of several thousand words is not at all unreasonable for an all-purpose instrument. Hence, about 10^5 flip-flops or analogous elements would be required! This would, of course, be entirely impractical.

It's hilarious to read this comment from almost eight decades ago about how 10^5 flip-flops are entirely impractical. 10^5 flip-flops is about 12.2KiB of memory. The browser tab you're using to read this alone is likely consuming three orders of magnitude more in RAM.

4.5. Inasmuch as a great many highly important classes of problems require a far greater total memory than 2^12 words, we now consider the next stage in our storage hierarchy. Although the solution of partial differential equations frequently involves the manipulation of many thousands of words, these data are generally required only in blocks which are well within the 2^12 capacity of the electronic memory. Our second form of storage must therefore be a medium which feeds these blocks of words to the electronic memory. It should be controlled by the control of the computer and is thus an integral part of the system, not requiring human intervention.

Even today, the "working set" of programs in execution is often much smaller than the size of complete data or even the complete program. By using cheap secondary storage which can load data into memory when required, the storage needs of the system can be met. This concept is still in use today as a combination of swapping and demand paging.

The medium should be capable of remembering very large numbers of data at a much smaller price than electronic devices. It must be fast enough so that, even when it has to be used frequently in a problem, a large percentage of the total solution time is not spent in getting data into and out of this medium and achieving the desired positioning on it. If this condition is not reasonably well met, the advantages of the high electronic speeds of the machine will be largely lost.

This paragraph describes the I/O bottleneck and we still deal with this even today, maybe in different ways. CPUs have gotten significantly faster but memory and disk latency have not improved as much. This means that the throughput of many programs is I/O bound or memory bound.

Number System

5.2. In a discussion of the arithmetical organs of a computing machine one is naturally led to a consideration of the number system to be adopted. In spite of the longstanding tradition of building digital machines in the decimal system, we feel strongly in favor of the binary system for our device. Our fundamental unit of memory is naturally adapted to the binary system since we do not attempt to measure gradations of charge at a particular point in the Selectron but are content to distinguish two states. The flip-flop again is truly a binary device. On magnetic wires or tapes and in acoustic delay line memories one is also content to recognize the presence or absence of a pulse or (if a carrier frequency is used) of a pulse train, or of the sign of a pulse.

...

Hence if one contemplates using a decimal system with either the iconoscope or delay-line memory one is forced into a binary coding of the decimal system—each decimal digit being represented by at least a tetrad of binary digits. Thus an accuracy of ten decimal digits requires at least 40 binary digits. In a true binary representation of numbers, however, about 33 digits suffice to achieve a precision of 1010. The use of the binary system is therefore somewhat more economical of equipment than is the decimal.

That explains the odd choice for 40-bit word size.

Their previous machine ENIAC was a base-10 machine. Even though binary computers seem ubiquitous today, that wasn't the case in the 1940s. When we look at it through the lens of the smallest parts of the computer, it makes sense that the system should be binary.

5.3. Several of the digital computers being built or planned in this country and England are to contain a so- called “floating decimal point”. This is a mechanism for expressing each word as a characteristic and a mantissa—e.g. 123.45 would be carried in the machine as (0.12345, 03), where the 3 is the exponent of 10 associated with the number. There appear to be two major purposes in a “floating” decimal point system, both of which arise from the fact that the number of digits in a word is a constant, fixed by design considerations for each particular machine. The first of these purposes is to retain in a sum or product as many significant digits as possible and the second of these is to free the human operator from the burden of estimating and inserting into a problem "scale factors"—multiplicative constants which serve to keep numbers within the limits of the machine

Today we use binary instead of decimal for storing mantissa and exponent. The standard for floating point numbers IEEE 754 was formalized in 1985 and FPUs don't become mainstream in PCs until c. 2000s. It seems rather odd because scientific computing heavily relies on "real numbers" for computations which are tricky to do with just integers.

There is, of course, no denying the fact that human time is consumed in arranging for the introduction of suitable scale factors. We only argue that the time so consumed is a very small percentage of the total time we will spend in preparing an interesting problem for our machine. The first advantage of the floating point is, we feel, somewhat illusory. In order to have such a floating point one must waste memory capacity which could otherwise be used for carrying more digits per word. It would therefore seem to us not at all clear whether the modest advantages of a floating binary point offset the loss of memory capacity and the increased complexity of the arithmetic and control circuits.

von Neumann wasn't entirely sold on why we might need floating-point numbers. He was quite vocal in his critique of floating-point numbers. For better or worse, floating point is now a ubiquitous number type in most systems.

In another paper, we find von Neumann's even sharper critique of floating-point:

"Besides, the floating binary point represents an effort to render a thorough mathematical understanding of at least part of the problem unnecessary, and we feel that this is a step in a doubtful direction."

There may have been some truth to this argument. Personally, I've spent days trying to correctly round off floating point numbers. Read more about floating point numbers here.

Unrelated: Ever wondered why Linux systems calls do not provide seconds as a floating point number but instead provide seconds mtim.tv_sec and nanoseconds part mtim.tv_nsec separately? OS like Linux still use integers to approximate real numbers using scale factors for various reasons and the use of floating-point is largely prohibited in the kernel.

These desiderata must, however, be considered in conjunction with some further comments. Specifically: (a) x and y themselves are likely to be the results of similar round-offs, directly or indirectly inherent, i.e. x and y themselves should be viewed as unbiased n-digit approximations of “true” x′ and y′ values; (b) by talking of “variances” and “means” we are introducing statistical concepts. Now the approximations which we are here considering are not really of a statistical nature, but are due to the peculiarities (from our point of view, inadequacies) of arithmetic and of digital representation, and are therefore actually rigorously and uniquely determined. It seems, however, in the present state of mathematical science, rather hopeless to try to deal with these matters rigorously.

Imagine mathematical genius from 20th century suggesting it's hopeless to deal with round-off errors from successive rounding operations. This is truly a hard problem to solve, just imagine a basic scenario like storing an order for multiple items.

| Product | Rate | Qty | Line Total | Rounded Line Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | 1.555 | 7.0 | 10.885 | 10.89 |

| Zinc | 2.555 | 11.0 | 28.105 | 28.11 |

| Grand Total | 38.99 | 39.00 |

If you have to round off to 2 digits, where should you round these numbers off? Rates? Line total? Grand total?

- If you round off the rate then rounding error will grow with quantity, so it's usually out of the picture.

- Rounded line total and the ground total can always be off by up to 1 cent. Is it biased? For which side?

There is no "correct" answer. You just have to pick one method and stick with it. This example doesn't even consider the intricacies of floating-point numbers which can not represent certain real numbers so it has additional representation error.

If you think fixed-precision numbers can save you somehow, boy do I have some news for you.

>>> # This is Python REPL

>>> from decimal import Decimal

>>> Decimal("1") / Decimal("3") * Decimal("3") == Decimal("1")

False

Consequently, multiplication and division must unavoidably be replaced by the machine by two different operations which must produce n-digits under all conditions, and which, subject to this limitation, should lie as close as possible to the results of the true multiplication and division. One might call them pseudo-multiplication and pseudo-division; however, the accepted nomenclature terms them as multiplication and division with round-off. (We are now creating the impression that addition and subtraction are entirely free of such shortcomings. This is only true inasmuch as they do not create new digits to the right, as multiplication and division do. However, they can create new digits to the left, i.e. cause the numbers to “grow out of range”. This complication, which is, of course, well known, is normally met by the planner, by mathematical arrangements and estimates to keep the numbers "within range".

This paragraph describes what we now refer to as "overflow" errors. Trying to keep numbers within range while doing arithmetic operations is possibly another major source of bugs even today. Leaving this problem entirely to "planners" doesn't always work out, humans have lost a rocket due to overflow error.

Debugging

4.8. There is another highly important part of the input-output which we merely mention at this time, namely, some mechanism for viewing graphically the results of a given computation. This can, of course, be achieved by a Selectron-like tube which causes its screen to fluoresce when data are put on it by an electron beam.

Debuggability is an essential property of complex systems. Debugging isn't just a process of removing faults from a system, it's how you truly understand what is going on under the hood, which may or may not match your understanding. e.g. When I use strace to understand what a program is doing, I am not always looking for any faults, sometimes it's just a process of understanding what's going on.

When a problem is run for the first time, so that it requires special care, or when an error is known to be present, and has to be located—only then will it be necessary as a rule, to use both machines in parallel. Thus they can be used as separate machines most of the time. The essential feature of such a method of checking lies in the fact that it checks the computation at every point (and hence detects transient errors as well as steady-state ones) and stops the machine when the error occurs so that the process of localizing the fault is greatly simplified.

Interesting. They use two machines to see if they always produce the same outcomes at every stage. We can find similar systems that require high redundancy and reliability, e.g. nuclear reactors, computers in space, and autonomous vehicles.

Secondly, they pause the execution so a planner can inspect the error. Sounds familiar?

The method of localizing errors, either with or without a duplicate machine, needs further discussion. It is planned to design all the circuits (including those of the control) of the computer so that if the clock is stopped between pulses the computer will retain all its information in flip-flops so that the computation may proceed unaltered when the clock is started again. This principle has already demonstrated its usefulness in the ENIAC. This makes it possible for the machine to compute with the clock operating at any speed below a certain maximum, as long as the clock gives out pulses of constant shape regardless of the spacing between pulses. In particular, the spacing between pulses may be made indefinitely large. The clock will be provided with a mode of operation in which it will emit a single pulse whenever instructed to do so by the operator. By means of this, the operator can cause the machine to go through an operation step by step, checking the results by means of the indicating-lamps connected to the flip-flops.

This is similar to modern-day debuggers which let you step through your program one instruction or one line at a time.

When the cycle time for writing and executing a new version of the program is high, trying out random hypotheses until it works was not a practical approach. Today, with modern hardware and fast iteration cycles we can get away with not even using debuggers for most bugs.

Epilogue - Eight Decades Later

This is how von Neumann's architecture is taught in schools today. The famous Big-Oh notation is also based on a similar model of computer. However, after eight decades of evolution, the underlying hardware is completely different from this model.

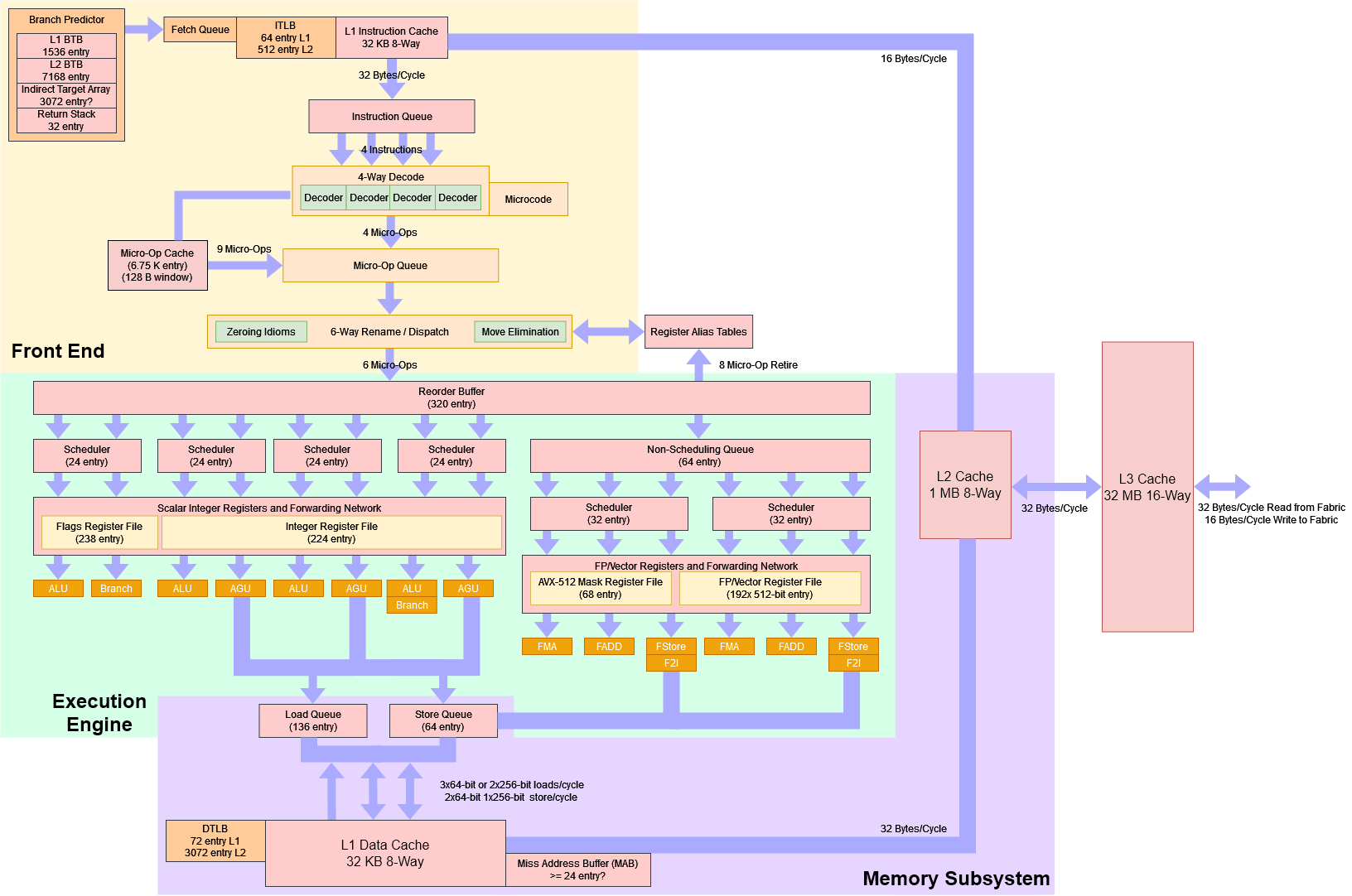

There is immense pedagogical value in our simple block diagram of von Neumann architecture, but let's be real here, even the original implementation of von Neumann architecture is not that simple. Let's take a look at this block diagram of modern Zen 4 architecture.

Image from Chips and Cheese.

In modern CPUs, NOTHING is straightforward.

- Instructions don't execute one at a time, 100s of instructions can be in flight at any given time.

- There is wild speculative execution going on in every component where it's feasible:

- Conditional branches are predicted using branch predictors long before they are actually evaluated.

- Many (typically 2 to 8) independent instructions can execute in parallel, on a single core.

- Stale memory values are used hoping they won't change, if they change CPU just rolls back the incorrect computation.

- Your memory access patterns are predicted by multiple pre-fetchers who issue the next memory access before your code issues them.

- Memory accesses can vary from less than one nanosecond (L1 hit) to 300,000 nanoseconds (Page fault + load from SSD).

- Hardware assists with virtual memory implementation using TLBs and paging.

- There are vector units to do single operations on multiple data aka SIMD.

- Oh, and there are possibly 100s of cores, all doing the same thing while trying to present a coherent view of the system.

- Oh, and there can be more than 1 such chip on the same board in NUMA configuration.

*mindblown.gif*

While computer architects ensure that you always get the expected behavior as per specifications, they can't do the same to guarantee performance. One needs to understand all the underlying components to a reasonable degree to truly utilize the capabilities of modern hardware, otherwise, we're doomed to use compute clusters for problems that can be solved using a single laptop. In the words of Paul Barham:

You can have a second computer once you've shown you know how to use the first one.

- - -

References/Further reading/Inspiration/Misc.:

- Original paper

- Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach

- Bryan Cantrill on Adaptive Replacement Cache

- The Future of Computing: Logic or Biology

- Halt and Catch Fire

- The Soul of a New Machine

Shower Thought: Who will "flip" von Neumann architecture and its eight decades of evolution?

I am kind of a noob on this topic, so if you found any typo or factual error in this post, please send a correction on GitHub ("source" in the footer) or via email.